The unauthorized entry of a suspected Chinese surveillance balloon into American airspace has provided a unique opportunity to examine the ability of Washington and Beijing to handle diplomatic crises. The incident leaves us wondering how the United States can better understand Chinese bureaucratic structure and decision-making and thus more effectively modulate its responses to unforeseen events. How will the two countries deescalate tensions when something more serious than a rogue balloon agitates the relationship? As the ability to interpret signaling accurately and maintain de-escalatory communication between the United States and China become more critical, so too will understanding the answers to these questions.

In an interview conducted by Oriana Skylar Mastro on April 13, Tyler Jost and Susan Thornton help contextualize the spy balloon incident within China’s bureaucratic decision-making.

Transcript

ORIANA SKYLAR MASTRO: Hi, my name is Oriana Skylar Mastro. I’m a center fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University and a courtesy assistant professor of political science at Stanford, as well as a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. On behalf of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, I am so pleased to welcome our viewers to a discussion of the spy balloon incident, crisis management, and implications for U.S. China relations.

I’m joined today by Tyler Jost, assistant professor of political science at Brown University, and Susan Thornton, who’s a senior fellow at the Yale Law School China Center and previously acting assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. Thank you both for joining me for this discussion.

SUSAN A. THORNTON: Great to be here.

TYLER JOST: Thank you very much.

MASTRO: Yeah, as a starting point, just in case our viewers hadn’t been paying attention and hadn’t heard the numerous stories and coverage of this incident, maybe we can start with you, Susan. Can you just give us a few sentences as the lead diplomat of this group of what we should be most focused on in the order of events between the United States and China over this incident?

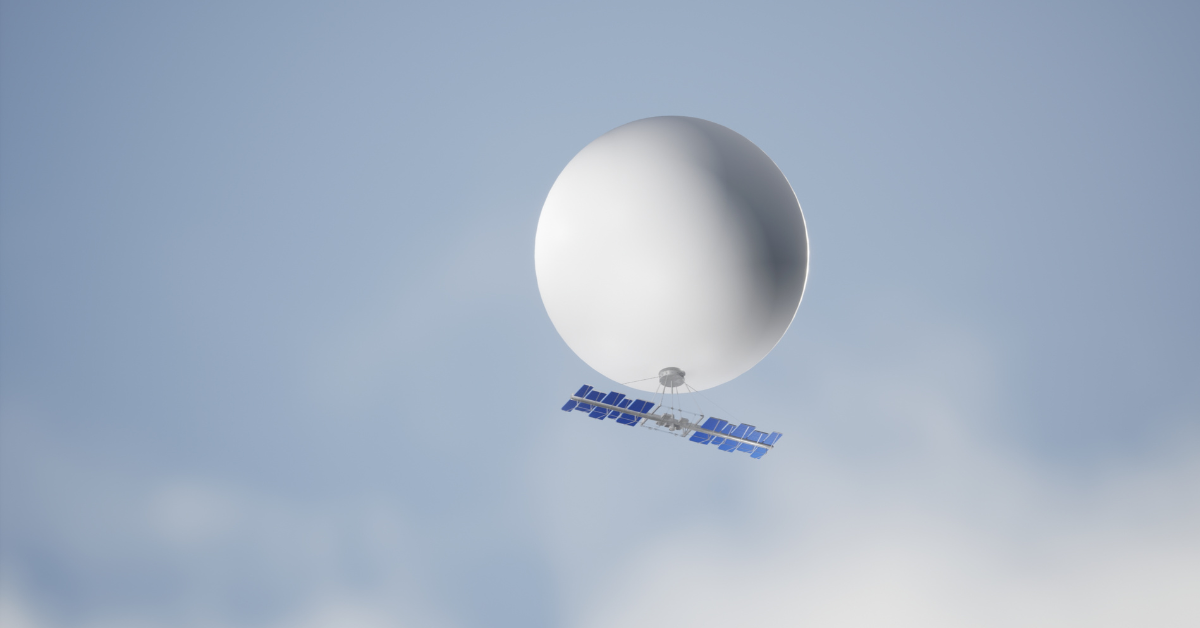

THORNTON: Yeah, well, just to recap really quickly, back in early February, and now we’re recording this in mid-April, so it’s been a couple of months, but just to recall, the Chinese sent a very, very large balloon with a lot of intelligence gathering apparatus attached to it in near-Earth orbit over the United States in U.S. airspace, and it was drifting for a long time from Alaska over Canada finally to Montana, where a local Montanan citizen spotted it, reported it to the newspaper. It went public.

There was a very large orb in the sky visible, and at that point there was quite a bit of attention being paid then by Congress, by a lot of people in the U.S. administration, attempts to get in touch with the Chinese to, you know, find out what this is, what are they doing? Why is this thing lingering over the United States? Not really got much of a response from the Chinese, which I think we will talk about in this episode. But then proceeded to watch as the balloon kind of lingered over Montana and finally drifted out over South Carolina, where it was, of course, shot down, recovered. And now it’s been in the hands of the FBI Investigative Service to try to figure out what was going on.

There’s been a lot of speculation about a lot of aspects of this, but we actually don’t have a lot of hard facts. I think it’s pretty clear that, you know, it was a spy apparatus. It was in U.S. airspace. That’s a violation of sovereignty. There was poor communication. It created a crisis which probably should have been avoided. And we missed an opportunity to probably create a new norm around this kind of episode going forward, which is unfortunate. And I’ll leave it leave it there for you to take up as you will, Oriana.

So, what was your sort of impression when this story broke about why it created such an incident between the two countries?

JOST: Well, as Susan said, I think it in very visceral terms, posed a question to the United States, which is, what threshold of espionage and intelligence collection we’re comfortable with accepting. Generally speaking, it’s accepted that states spy on one another. But there can be limits imposed by both sides on how much activity they’re willing to prevent.

Something like this, which, as Susan mentioned, was a violation of U.S. sovereignty, does potentially cross a threshold, and as the United States sort of decided to intervene here or establish here, it was not willing to accept the idea that there would be aerial air balloons collecting intelligence over U.S. airspace in such a flagrant manner such that average U.S. citizens could look up in the sky and see it.

MASTRO: Mm hmm. Yes, I do think we’ll get back to that, how the domestic politics plays out, because I think that was a big part of it, as you know, that people could actually see this happening while maybe some of the other discussions about China are not so sort of visible or visceral to the American people.

Susan, can you give us a little bit about the norms around this? I know the Chinese, you know, people ask me all the time in the media like, you know, does the United States have programs like this, is everyone does flying balloons around and everyone else’s airspace? Like what is the actual international law that would cover something like this?

THORNTON: Yeah, well, it turns out that there aren’t a lot of norms in this in this exact space, which is part of the confusion and quandary, I think, around this incident. As you remember, after this balloon was shot down, it was discovered that there were a number of other obstacles or balloons or objects floating around in the in a similar space in the stratosphere. And those were also shot down. And it turned out, I think we found out eventually that one of them was likely a kind of a hobbyist balloon. It’s not really clear what the others were, but I there’s a space in in sort of the airspace above where commercial air airliners usually fly in below outer space, right, where it’s not totally clear what the norms are. And so that was a space that the Chinese were exploiting.

You know, I think that it’s also the case that these have been balloons that have been frequently flying in the last few years. And there were a number of them that flew over the U.S. earlier that nobody apparently did anything about—whether we knew about them or not, I think probably we did—but they were also flying over other countries’ airspaces, which we also knew about.

So it’s something that’s been happening for at least a few years. And not much has been done about it. And I think that is the space where there’s an opportunity to do something about it. If it hadn’t been quite as, you know, quite as big a kind of kerfuffle as it was.

MASTRO: Now I have to sort of just come in here and just mention that the Chinese did sort of make this comparison between their balloon program and U.S. surveillance and reconnaissance against China. Like how many times U.S. aircraft or ships are gathering information against China? And I always find it necessary, if I can get on my soapbox for a second, to say that, you know, the United States is conducting those types of operations in international airspace, in international waters, which I think is fundamentally different than what the Chinese were doing, which was over U.S. territory, though the Chinese might see it differently, I think, you know, it’s the activity itself and not necessarily where the activity is taking place that is so important.

So, you know, a lot of the reports told us that this wasn’t the first time that the Chinese had sent a balloon over the United States like this. You know, we don’t have a lot of details or live statistics about how many times. But Tyler, like you mentioned, you know, this did become a bit of an incident. It was more of a focus in the domestic discourse in the United States. Do you think it’s important to ensure that these things don’t escalate to this type of level? You know, should it have not been a flashpoint between the two countries? And if not, how do you think we can prevent these types of incidents from becoming flashpoints or crises?

JOST: I think that there have to be really clear lines established by both sides what they’re willing to permit. You could have, if both sides agree to it, you could have some sort of Open Skies program in which both sides agree that it’s permissible for you to collect intelligence in aircraft on military facilities and the other side. Something like this was proposed during the United States under the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

But it’s unlikely in my mind that China is going to permit such reciprocal action, nor is the United States really interested in it. So if that’s the case, then it needs to be clear in the minds of decision makers, both in Washington and in Beijing, that this type of thing is not going to be permitted, and the United States is going to follow a similar course should another spy balloon show up inside of its borders.

MASTRO: So for both of you, if you had to, you know, just choose one side, do you do you think that the United States made too much of a big deal out of this, or not enough of a big deal out of it? Just like a one sentence answer, because I’m going to ping you on it to give further [explanation]. But if you had to choose one of those sides, which would it be?

THORNTON: Made too big a deal out of it and missed an opportunity to turn it into something positive.

MASTRO: Too big of a deal. So Susan’s on too big of a deal. Tyler?

JOST: For the sake of a good discussion, I’ll say that it was not too big of a deal. It was the appropriate response.

MASTRO: Well, okay, So I will tell you, this is one of my favorite things to do with panelists. Are you ready? We’re going to we’re going to play devil’s advocate in which I make each of you argue the opposite of what you think, in terms of what would the other side say to that argument.

So, Susan, can you try to make the argument—of course, we all know that you don’t agree with this position—but what would the argument be for why the U.S. response was appropriate? And then Tyler, can you tell us what the argument would be for of why this was such a big deal?

JOST: Sure.

THORNTON: Sure. So I’ll go first. So why the reaction was appropriate or at least understandable would be that the U.S. tried to communicate with the Chinese to get them to get the balloon out of our airspace, to remedy their, you know, quote unquote “mistake” that they claimed had had happened. You know, the balloon had been abducted by the westerly winds and blown off course. So we did try to get in touch with them.

We got no response from the Chinese side for a long time. Meanwhile, media pressure is building on politicians, of course. In addition to that, there’s apparently a lot of evidence that the balloon was loitering over sensitive sites, sensitive military sites in the middle of the country. And there was a lot of, you know, suspicion, at least that that was not accidental or that was not part of the sort of being blown off course, the fact that the balloon was being blown off course and then loitering over a sensitive site.

So all this time, again, not getting any response from the Chinese side, not being able to ascertain, you know, intentions or the future trajectory of this thing. I think it’s completely understandable under pressure. And sort of also in the environment we have currently in the U.S. of sort of political weaponization of these things, I think it’s perfectly understandable.

And the Biden administration was prudent. They waited until it had drifted all the way off the coast and then proceeded to take it down, you know, telling the Chinese that that’s what they were planning. So I think all in all, it’s sort of an understandable response.

MASTRO: Don’t worry. I’ll let you also voice to the other view in a second.

THORNTON: That’s going to argue my point valiantly. I know it.

JOST: I’m going to be able to live up to what Susan has just done for myself.

MASTRO: Yeah. So, you know, I always think it’s important, a lot of these issues, I think one of the main reasons, the main ways of making it so it doesn’t become politicized is so that everyone has an understanding that multiple viewpoints are valid even if we find the logic of one stronger than the other. So, Tyler, can you give us the argument for why the response was not appropriate?

The United States made too big of a deal out of this.

JOST: Right. I mean, I think the most important thing to think about here is the cost that came to the United States. Right. So there was some opportunity, as Susan was alluding to, to diplomatically engage. This came right before an anticipated high-level dialog between the United States and China, which was delayed and the quality of dialog degraded as a result of the U.S. decision.

And so if that cost is sufficiently high, then we have to ask ourselves, okay, could the United States have pursued something else? Could it have allowed the balloon to continue on its course? And in that scenario—and obviously the whatever intelligence was collected was already lost—but the United States did take measures because it was able to identify the balloon’s path in order to mitigate whatever loss might have been occurring.

So at that point, shooting the balloon down only serves as some sort of signal for establishing red lines for the future. And if it was possible to also achieve those red lines through diplomatic dialog, then maybe shooting it down sort of incites a response, provokes a response in Beijing that is ultimately not worth what we got out of it.

MASTRO: Okay. All right. So, you know, I made you kind of go against what you were thinking. So I’ll give you the opportunity now, Susan, anything you want to add to the you know, why did the United States make such a big deal out of this? And Tyler, anything you wanted to add to Susan’s response of why the U.S. response is appropriate?

THORNTON: Well, I think there was an opportunity to show some leadership and to make diplomacy, you know, to firmly plant the diplomatic flag here on this one. It wasn’t, you know, an overly sort of threatening act. It was something where the Chinese were clearly in the wrong and they admitted as such. I mean, in fact, the Chinese made, to my recollection, the first statement of regret from the official podium that I can recall in my entire career.

So, you know, I think they were really looking to de-escalate. They were trying to smooth the way for the Blinken visit. That gives the United States some leverage in the relationship, which is something we’re always looking for. And, you know, to squander that and then shoot the balloon down. It’s you’re basically giving the Chinese leverage, which they then subsequently used to roll out a kind of a campaign around the world to say, look how, you know, militant and lacking in confidence the United States is they had to shoot down a balloon. So I think, you know, the cost-benefit for me was just not there.

MASTRO: And if we had that incorrectly, Susan, what do you think we should have used that leverage for? What would have been your first ask?

THORNTON: Well, I think when Tony Blinken got to Beijing after this whole episode, he certainly could have, you know, put forward look, there’s you know, instead of sort of demanding that they promise never to send a balloon over the United States again in order to have him come for the meeting, he could have gone to the meeting and then said, you know, we’re going to set up a system here to govern, you know, this airspace, and make sure these objects are not flown, that there are not these dangers to commercial aircraft and other things up there, and that this is something that really needs to be addressed.

I mean, it would have been a good thing to try to, you know, get that laid down, you know, first between the U.S. and China and then extend it to an international norm. I mean, I think that would really have accomplished something rather than where we are now, not talking to each other, both kind of retreating to our corners and not clear when we’re going to have any diplomatic communication again.

MASTRO: So before we get to the communication channels, Tyler, I want to give you an opportunity. Is there anything you want to add on the sort of appropriateness of the U.S. response that you think we haven’t covered?

JOST: Sure. I mean, I think, Susan, Susan obviously raises a very important point regarding the way that the Chinese state responded to the incidents. That being said, it was also presented alongside what was really a boldfaced lie, right. Insinuating that the balloon did not have some sort of intelligence collection capability associated with it, I think, made in the eyes of contemporary decision makers and myself, it a little bit difficult to see the statement of regret in the same lines.

And then ultimately, there is a question about U.S. credibility, if the United States is not willing to impose costs, if China takes these types of actions. So that’s where I come out of this.

MASTRO: All right, good. So let’s move on a bit to talk about these communication channels, because this is a hot topic. Susan mentioned that we don’t have a lot of, you know, diplomatic interaction with the Chinese. We know that during the Cold War, the United in the Soviet Union had developed various mechanisms for crisis communication and standards preparation, operation to keep the Cold War cold.

I remember I was doing archival work for my first book and reading through some of the archives in the Vietnam War. It was so surprising to me the really direct conversation that the United States and Soviet Union would have about when the United States was going to bomb parts of Vietnam.

So can you tell us a bit about the state of U.S.-China diplomatic relations? Can you tell me a bit about what is the state of the communication between the United States and China? And where should it go?

JOST: Sorry, Oriana, was that for me or for Susan?

MASTRO: Why don’t we start with Susan and kind of where things are compared to, you know, where things were with the Soviet Union. And then maybe, Tyler, you can offer some views on how we can get to a better place.

THORNTON: Yeah. I mean, I think that the communication between the U.S. and China is just filled at this point with mutual suspicion and kind of a daily resistance to talking, to understanding one another. And the real, you know, expectation that the other has just malign intentions toward the other. And that’s a real difference.

There’s also a problem that I see in inequality between the U.S. and China in the sort of confidence level in communications. If you compare U.S.-China communications with the U.S.-Soviet communications with which I have some familiarity, had worked in the former Soviet Union and in Russia. The Russians see themselves much more on an equal footing with the United States in diplomatic encounters. I mean, strange as it may seem, we think of China as being so much stronger, you know, in many respects. And the Soviet Union was even at the height of the Cold War. But the Russians really had a kind of confidence to their diplomacy that you never see, and I’ve never seen with China.

I mean, if you just look at kind of bridge-to-bridge communications between Soviet and U.S. mariners out in like the Mediterranean during the height of the Cold War and the kinds of exchanges they had. I mean, it was real bravado and a lot of, you know, kind of ribbing and joking in a very kind of confident way. And we just don’t have that kind of same rapport between the U.S. and China.

And in fact, now, as you mentioned, Oriana, I mean, diplomatic communication is almost negligible. And I think the Chinese see these efforts that the US is making to so-called to keep the lines of communication open or set up crisis management channels, they see that as a disadvantage to China, which is, you know, a real problem in dealing with these kinds of incidents that we’ve been talking about.

MASTRO: So, Tyler, how do you, I know this is probably a years ago, but I remember reading a paper of yours about sort of diplomatic interactions between China, high level visits, right. Do you have any sort of interesting comparisons to offer to us about, you know, how this is similar or different to maybe even the U.S.-Soviet Union communications, but other comparisons and then ideas for how to try to move the relationship forward?

JOST: Well, frankly, I’m not as familiar with U.S.-Soviet military to military communications or crisis communications. On the U.S.-China side, though, it is striking that this is quite similar to other crises we’ve seen in the past. The style of communication and the inability to get messages at lower levels of government to Beijing during the recent balloon incident is very reminiscent of what happened in the 2003 crisis.

You can draw similar analogies if you go back further in history, right? So there’s a similar story during the 1969 Sino-Soviet border crisis in which senior levels on the political side of the Soviet Union tried to reach decision makers in Beijing, both Mao and Zhou [Enlai], but was shot down by telephone operators who refused to patch the call through. So it makes me somewhat pessimistic. I’ll be more pessimistic than I was when I wrote that paper. As a first-year graduate student that you read.

About whether or not the normal types of hotlines and low level horizontal communications between the two sides are really the best way, well, they might be the best way, but are a realistic way in which they can diffuse crises in the future? It seems to me that there’s something there’s something going on in the Chinese side, which is not necessarily going to be fixed by the establishment of some sort of mechanism or protocol, because one does exist. We know that since 2007 there’s been a military hotline between Beijing and Washington, but it reportedly was tried trying and tried to use it during the recent crisis. And much like 2001, before the hotline had been established, Beijing just refused to take the call.

MASTRO: So I have now what I like to call the Lightning Round of a series of questions, some very serious, some less serious, but I think equally as interesting and important about this balloon incident. And then we will conclude with the last lightning round question. I’ll tell you now is, is there anything that you want to add that you think hasn’t been covered in this conversation? So that is kind of a catch-all for you to talk about whenever you want to talk about. But I have like five questions here. All right. Are you guys ready?

JOST: And by lightning round, does that mean you want, like 5 second responses?

MASTRO: Oh, like 10 to 15 second responses. I mean, we are kind of academics after all. So maybe we’ll switch off. When I ask the question first, Susan responds. The second question, Tyler responds first. You both will respond, but Susan responds first. First Susan, and then go back and forth.

Okay, Susan, should the United States have its own balloon program?

THORNTON: Oh, gosh. Well, you know, I think the answer to that depends on what it is that we think we can gain from this versus what would be lost. And I would probably say that, you know, again, the cost-benefit for me is not there.

MASTRO: Tyler.

JOST: I’ll be uncharacteristically un-academic.

MASTRO: Okay. Now second question, should we shoot down all the balloons we see?

THORNTON: No!

MASTRO: Tyler.

JOST: Probably not.

MASTRO: If the United States did establish a new military force known as the Balloon Force, what do you think that uniform should look like?

THORNTON: The Michelin man.

JOST: The costume from the Up character in the Pixar movie.

MASTRO: Fantastic. All right, Now we’ve got we both sort of I think we’ve all agreed that cutting diplomatic ties in this instant was not a good idea. When do you think the United States should cut off diplomatic engagement with China? Are there certain conditions you have in mind? Or certain levels, like if they did this then sure, it makes sense. Or do you think it’s never a tactic the United States should employ?

JOST: Basically never. Someone wrote a book about maintaining diplomatic ties and communications during wartime.

MASTRO: Brilliant book, some would say.

THORNTON: I think it was called The Costs of Conversation.

MASTRO: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So that’s a great answer, everyone. The answer is, read Oriana Skylar Mastro’s book The Costs of Conversation.

THORNTON: You better buy it.

MASTRO: Yeah, buy it. And then read it. Susan, you mentioned China was sorry. And Tyler, you kind of said, yeah, they said they were sorry, but it’s kind of like how my two-year-old apologizes. Like, yeah, you know, then they said, but they didn’t do it anyway. So was China sorry enough?

THORNTON: It should have been enough to get us to engage diplomatically, in my view. Now, they’ll never be regretful over anything ever again.

JOST: I would have liked to see more sincerity on the Chinese side.

MASTRO: If this balloon incident becomes a major Hollywood movie, which nowadays, with all the crap that you can see on streaming services, this might happen. Who do you think should play the balloon hero in this movie?

THORNTON: Arnold Schwarzenegger.

JOST: But who is the balloon hero, though?

MASTRO: They’re probably going to, like, shoot him in a jetpack towards the balloon.

THORNTON: The Terminator, clearly.

MASTRO: Versus a missile. Like, it’ll—

JOST: Be something I mean, that’s what makes the whole situation potentially less escalatory, because it was unmanned.

MASTRO: But here for some reason, there’s some talk, you know, time is running out and they’ve got to shoot a man into—you know, who is the balloon hero?

JOST: Who’s the balloon hero… Let’s say Jim Carrey.

MASTRO: Good. I always want Liam Neeson because, like Liam Neeson is my favorite action star. All right.

We have 2 minutes left. Is there anything here? And we can start with Tyler and then end with Susan? You want to add to this discussion that you think the viewers should know about the balloon incident and crisis management communication between China and the United States more broadly?

JOST: Sure. I mean, the one thing that we didn’t really touch on very much was the bureaucratic coordination side of things. And this is something, I think Susan alluded to it a little bit, but I very much agree here.

It does seem to me that there was some sort of miscalculation or miscommunication inside of the Chinese government, characteristic of what happened in the 2001 EP-3 crisis, which I think, going back to our conversation about how you establish hotlines or channels of communication to keep bilateral relations stable in the event of something like this happening in the future, it is a real challenge, I think. And I think from Washington’s perspective, we should be planning and thinking about, how do you defuse crises, assuming that you’re not going to get low-level responses for potentially a couple of days?

MASTRO: Susan, last words.

THORNTON: Yeah, I mean, on that, you know, think about the media pressure and the timelines that are different between China and the U.S. That’s number one. Number two, diplomacy is not about truth. It’s about finding a way to manage the situation so you can maximize your interest at the end of the day. And so I think taking advantage of any opportunities, you know, in the current situation, which is pretty dynamic and pretty filled with tension, we need to do that.

MASTRO: I think that’s a perfect way to end this program. Thank you, Tyler and Susan, for joining me. We have covered a lot of different topics that hopefully give our viewers a sense of the strategic importance of this incident, as well as what it means for crises and flashpoints for the United States and China moving forward. Thank you.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity. Please refer to the video interview to ensure accuracy.